In the project Social objects for innovation and learning, we explore the role objects play in our everyday lives, at work and at home, in and through our interaction with other humans. The project will thus advance our understanding of objects as they feature in actual situations of human activity, by examining how objects are used, created, perceived, attended to, shared and understood across a range of different interactional contexts. Within the project we will pursue two key interests:

- how do objects support creativity and collaboration for innovation?

- how do objects mediate and support learning and instruction?

Classroom interaction

Kristian Mortensen

This project investigates participation in the language classroom, which has a substantial research tradition. The interest in participation rests on two assumptions: first, the notion of participation has been associated with students’ verbal and vocal conduct and it is assumed that getting access to turn-at-talk is essential for language learning. Second, that teachers and the ways in which they organize and manage classroom activities both facilitate and constrain student participation. More recently, and closely linked to the methodological approach within SOIL, studies have described how students’ (verbal and vocal) participation is embedded within their bodily conduct including orientation to material artifacts. Our current work includes teachers’ use of graphic structures as elicitation devices; (transgressions) of the moral order during pedagogical activities and bodily resources in and for repair sequences.

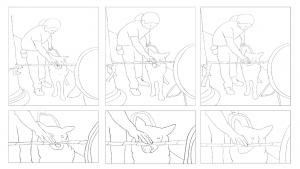

The Role Of Objects In Social Interaction

Chloé Mondémé

As part of the SOIL project, I am exploring the role objects play in everyday social interaction, and especially in interspecific interaction. In several data sets (ordinary domestic interactions, training situation, assistance dogs, etc.) I analyze and document the joint focused orientation to the material environment human and animal can share. Ordinary objects in the immediate surrounding like e.g. the leash, the bowl of food, the toy, etc. are resources that create and support mutual comprehension and action. Here again, we find patterns that are closely related to those found in an (only)human interaction.

Flight instruction and training

Maurice Nevile

This research is new in 2016, and is conducted in collaboration with a US colleague (Dr Bill Tuccio). It examines data of inflight interaction between instructors and student pilots, and is concerned generally with how people are taught and learn to use complex technologies in mobile environments. It seeks especially to target flight instructor effectiveness, and student radio communications training, towards creating an intervention program in line with the CARM model developed by Prof Liz Stokoe (Loughborough University, UK).

Photo: Matt Wells (Pilot)

What’s that chicken doing here?

Jeanette Landgrebe

In this project, we are investigating the social rules and practices in a lecture room. What happens when a chicken enters the classroom and acts as if “it” belongs to the group of students? And what happens when that chicken crashes different teaching sessions to say hello? For instance, one lecturer commented as a remark to his students who couldn’t stop giggling: “Well, haven’t you ever seen a chicken before”, and then he re-oriented to his teaching. Another teacher confronted the chicken and scolded: “This is a university.” But perhaps the most interesting element here is how the students themselves react to a new, strange-looking fellow student?

Forklift driver training and certification

Dennis Day, Kristian Mortensen, Maurice Nevile, and Johannes Wagner

This project involves collaboration with a local forklift training school, and explores how drivers of different levels of knowledge and experience are instructed and learn to drive forklift trucks in a simulated warehouse environment.

Areas of interest include:

- how drivers give warnings about presence and movement as trucks pass one another

- how instructors describe loads and how they should be lifted and moved

This collective project deals with the boundaries between body and objects, and how people can acquire so strikingly elaborated skills in using objects such that the borders of the body expand. Gregory Bateson (1973: 318) gives an example in his book Steps to an Ecology of Mind: “Consider a blind man with a stick. Where does the blind man’s self begin? At the tip of the stick? At the act of the stick? Or that some points halfway up the stick? ”

The Forklift project attempts to understand how bodily skills in using complicated machinery are built by learning to drive a forklift.

The project has been allowed to video record a complete training course for forklift operators at the Kolding AMU center. The project installed 15 cameras in the learning environment following three specific trucks with footage from several angles inside and outside of the trucks. The data cover 82 hours of forklift driving. The different camera angles are integrated into one video stream but each camera angle can be accessed individually. In collaboration with TALKBANK at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, SOIL has developed features where transcriptions can switch between different camera angles, a feature that hadn’t been added previously to any other transcription software.

After having spent half a year to edit and sync the video material, the project groups is now going to look at how truck operators learn to handle forklifts, how they get the feeling of how deep the load is, how high the fork is raised, etc. The project focuses on a type of learning that – unlike much school-based learning – is concerned with procedural knowledge, i.e. in the ways operators build body-based skills and competencies. The forklift project cooperates intensely with researchers from SDUDesign and collaborates with CROWN, an US forklift producer, about design and development of future forklifts.

Johannes Wagner presented the project at the yearly conference of Danish forklift teachers in August 2014. Kristian Mortensen and Johannes Wagner presented a paper on skill learning at a conference in Groningen, The Netherlands, in 2015, arranged a workshop in New Bremen, Ohio, and are currently writing an invited chapter about skill learning. Further papers are currently written by Day, Mortensen & Hazel; Day & Wagner, Nevile & Wagner; and Nevile.

Collaborative Designing and Making

Jeanette Landgrebe and Maurice Nevile

This project involves collaboration with local clothing designers and makers. It examines video data of interactions for custom clothing design and making, including meetings and fitting sessions involving designers, makers, and users. It is an environment rich with objects, as both tools and outcomes of collaboration, including fabric, pins, and scissors. One focus considers how participants use objects to organize and progress their joint activities, as they propose and agree on possible alterations to a dance dress.

Embodied breaching

Agnese Caglio

Agnese Caglio has a background as an industrial designer and studied IT Product Design at the University of Southern Denmark in Sønderborg. Her project is about breaching normally invisible bodily routines by modifying everyday objects. Agnese modified conventional cutlery (e.g. forks and spoons) such that they have a ring instead of a shaft. The redesigned cutlery can be attached to a finger. The material changes eating behavior. Eating routines do no longer work smoothly. The redesign challenges the motoric skills involved in eating. Children spend a long time on learning how to eat properly with a spoon or fork. The resulting highly automatized behavior and the work involved in it becomes accessible through the embodied breach.

The project investigates how people engage with unfamiliar objects, and learn to experience and to manage them. Agnese’s design interventions make the bodily routines and their relevance to everyday life visible as e.g. the compensatory strategies that subjects use to be satiated. Embodied breaching can develop into a design tool to create analytic distance to ‘seen but unnoticed’ embodied ways of handling material artifacts in daily life.

Objects and performance

Spencer Hazel (2015)

This line of investigation concerns the enactment of objects within theatrical performance, including their transformation from material resource to prop to socially situated object within a staged scene.

That Theatre Company

The study adopts an interaction analytic approach to investigate how theatre practitioners e.g. explore, discover, negotiate, learn and reproduce such representations of interaction. Producing recognisably realistic representations of social practices is part of what Burns (1972) has described as “authenticating conventions”, affording staged scenes credibility, as they draw on common-sense understandings of the social world that are shared by their audiences, including those members of the public who have more intimate knowledge of the settings being depicted.

In naturalistic performance, the appropriate use of objects (props) is one area that actors are required to get to grips with, as they work the objects into the course of the dramatic action, exploring how best to represent the authentic handling of objects relevant to the proceedings.

Why Not Theatre Company

The data instances where the actors work on enacting particular objects. By enactment, I mean here the bringing to life of a prop as a recognisable, situated object within a naturalistic representation of a particular activity. The way in which these members organize their engagement frameworks around an object transforms it from one class of object to another. For example, a generic plastic tube becomes appropriated first as a theatre prop, then subsequently enacted as a catheter, with members drawing on diverse pools of professional knowledge. These transformations are occasioned through changes in how the members handle the tube, and how they jointly organize themselves around the enacted object. By presenting such handling as an informed approximation of (medical) professional competence, the performers enact objects as recognisably authentic artefacts for the setting being portrayed, and consequently display to a viewer how such objects are implicated in the procedures at hand.

Patient education

Tine Larsen

Tine Larsen’s project is about disease-specific patient education, where patients with potentially life-threatening chronic diseases are trained to take responsibility for monitoring and treatment of their illness at home. Specifically, she works with self-managed oral anticoagulation therapy for patients with an increased risk of thrombosis (anticoagulant therapy) and automated peritoneal dialysis for patients with terminal renal failure (P-dialysis); both treatments involving technologically highly complicated medical equipment, which in itself can be dangerous if not used properly.

Tine described in her PhD project how patients were instructed to apply this equipment so they eventually were qualified to take it home and wouldn’t need to come so often to the hospital for treatment. She demonstrated how different instruction practices created various opportunities (and challenges) for the patients to follow the instructions and for nurses to understand patients’ understanding of the treatments, and ultimately to patients’ opportunities to learn.

Tine’s postdoctoral project examines how the different technologies’ physical properties and characteristics are relevant for the interaction, and how they together with the material environment shape instructions. Currently she focuses on how the immediate possibilities (for physical action that the medical technologies and objects allow due to ailment and treatment specific considerations) are differentiated, redefined and limited in and through interaction.

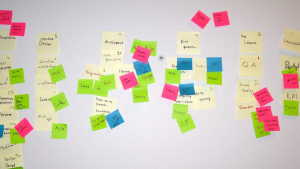

Post-it

Agnese Caglio, Jeanette Landgrebe, Trine Heinemann, Dennis Day, Johannes Wagner, and Kristian Mortensen

At the ALAPP conference in autumn 2014, the SOIL project organized a panel on Post-Its and works on a special issue of a journal to document the panel.

In design workshops and similar activities, ideas and keywords are recorded continuously on Post-Its and the small colored notes are placed visibly for others in the environment, moved around, merged and combined with other Post-Its and objects and also with other small texts on whiteboards or flipcharts. As texts are Post-Its interesting because they in themselves are no more than a keywords (‘pointers’) that refer to complex meanings and ideas that participants have formulated during the process.

But how ‘sticky’ are these complex meanings when Post-Its move around? Where do Post-Its go when the workshop or the creative process is over? An interesting example was the exercise when our current department was formed. Post-Its, yarn and other materials were put up on a bulletin board over a period. The employees’ areas of interest were successively written on the board. The passers-by could highlight network relationships and comment structure with colored pens. After a period the activity was abandoned. There had been formed a snapshot of many employees’ academic interests which was interesting, informative, and consequential. When the material was taken down these material correlates of all these networks disappeared. The material had fulfilled its creative purpose.

At the panel papers by Caglio, Landgrebe & Heinemann, Day & Wagner, and Mortensen & Brouwer were presented. A special issue, to be edited by Dennis Day & Johannes Wagner is currently being prepared.

Gem

Gem